Verify, Then Trust: A Smarter Approach to Mobile Forensics

In digital forensics, we always here the phrase "trust but verify." While this sounds good, it fundamentally misses the mark for examiners handling real-world cases. The phrase implies you should initially accept a tool's output or methodology as accurate, then confirm it afterward. This approach can create cognitive bias and puts your investigations at risk.

A more "forensically sound" approach to digital forensics seems like these words should be flipped: "Verify, and then trust".

Understanding Validation vs. Verification

Validation and verification are often spoken by examiners as if they are the same thing. My thought process has always been, you validate the PROCESS and you verify the RESULTS. Those are two separate things.

Validation: Proving Your Process Works

Validation answers a fundamental question: Does the tool or method actually do what it claims to do?

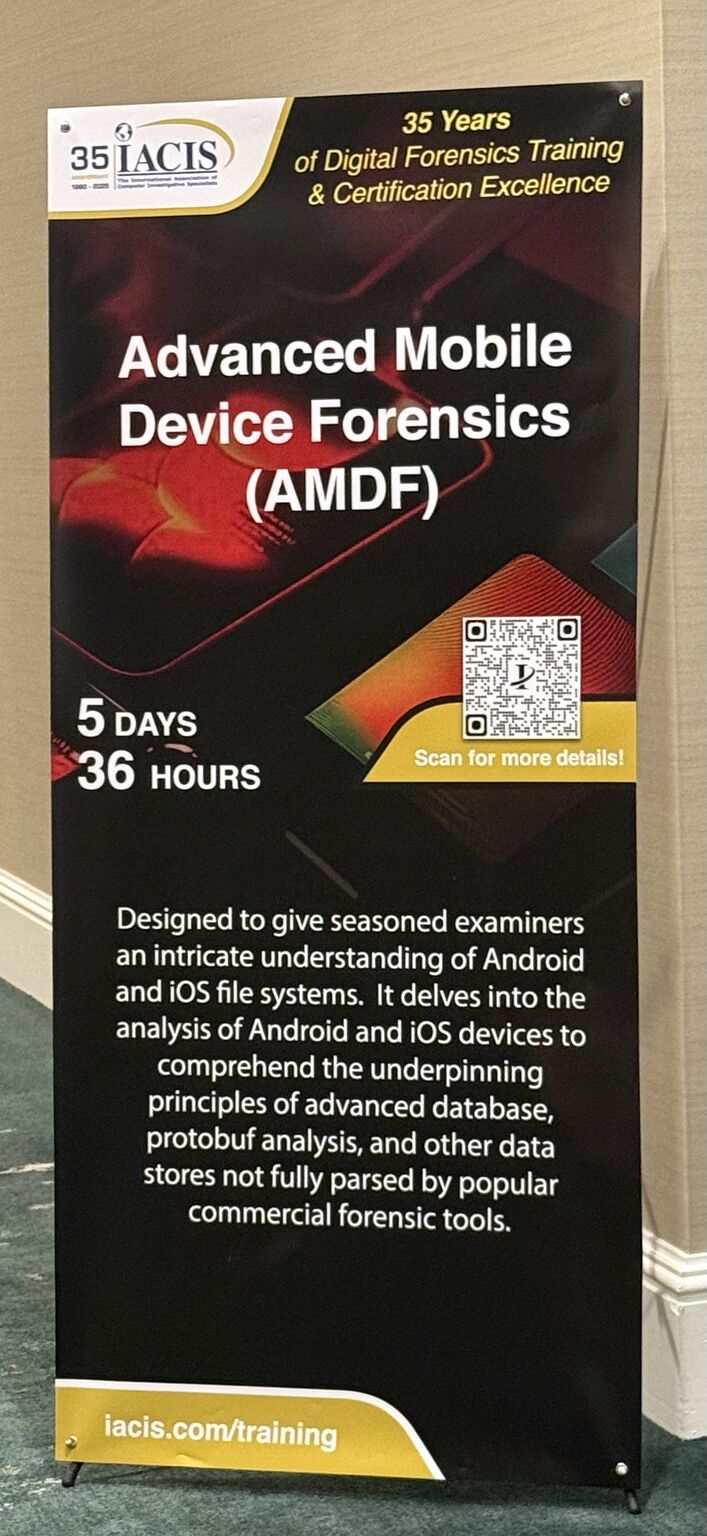

This isn't just about the software/hardware, it's about your entire process. Whether you're using commercial acquistition tools such as Cellebrite, Magnet or UFDAE or open-source parsing tools such as ArtEX or any of the wonderful LEAPPS, validation is a MUST:

Think of validation as stress-testing your foundation. You wouldn't build a house without first confirming your concrete can bear the load. Similarly, you shouldn't present forensic findings without first proving your methodology is sound.

Verification: Confirming What You're Seeing

Verification addresses a different question: Is this action or thing actually what I think it is?

Here's where many examiners make mistakes. For example, an examiner sees the red "X" next to a text message in their commerical tool of choice and concludes that message was marked for deletion by the user. Another example, an examiner notices a timestamp and assumes it represents when an event occurred and that the timestamp is stored in the database in UTC. The examiner then converts the timestamp to their timezone. Lets say the examiner changed the timestamp to UTC-4. But, what if the artifact was actually stored in the database in local time? With the conversion to UTC-4, that timestamp is no longer accurate. That examienr is making an interpretation without understanding how the data is stored on the device. Your forensic tool is making interpretations, and interpretations can be wrong.

Real-World Application: The Deleted Message Example

Let's examine this common scenario further that illustrates why verification matters:

Your tool shows a text message with a red deletion indicator. Most examiners would document this as "deleted message recovered." But what if that's not accurate?

The verification process should look like this:

- Locate the source data - Find the actual database or file containing this message

- Examine the raw data - Open the SQLite database or binary file outside the commerical tool and make sure you see the entire picture. Commerical tools don't parse everything in a database or other data struture.

- Understand the schema and flags of the database - Learn how the messaging app stores data.

- Cross reference with test data - Create your own messages on a test device. Now, delete them and run various other scenarios, document and compare.

You might discover that the "X" actually indicates something entirely different. What if the artifact is actually from the Write Ahead Log (-Wal) and was just not written to the main database yet? Without verification, you could be presenting evidence incorrectly.

Building Your Verification Toolbox

Test Devices: A HUGE part of the process

One of the most valuable resources for the verification process is a collection of test devices. Here's how to build your inventory:

Sources for test devices:

- Evidence and property rooms (devices past their retention period)

- Local jails(phones that were confiscated)

- Department upgrades (older agency phones)

- Your old phone

Setting up your test environment:

- Use devices running the same OS versions as your cases IF you can.

- Install the same apps you commonly see on devices you examine. Install apps that you are interested in seeing how it stores data.

- Create controlled scenarios (send messages, make calls, install/delete stuff)

- Document everything meticulously

The Reverse Engineering Approach

When you encounter unfamiliar data structures/flags or surprising results, have a reverse engineering mindset:

- Repeat the action - Perform the same behavior on your test device as what you expect the evidence device did.

- Extract and compare - Extract the data using the same acquistition tools you use everyday in your lab. Dont' deviate initially from what you normally do.

- Examine at the hex level - Look at the raw data in a hex viewer of choice when necessary

- Map the relationships/joins - Understand how different artifacts connect or join in the data structure

This process transforms you from someone who just reports what the tool outputs, to someone who truly understands the evidence.

Courtroom Confidence: Why This Matters

When you testify, you're not just presenting what your tool reported, you're staking your professional reputation on the accuracy of your findings. Defense attorneys are increasingly sophisticated about digital evidence, and they will challenge your methodology. And guess what, THEY SHOULD!!! The results you provide have the ability to change a lot of lives. Our job is to get it right, so the attorneys, judge and jury can form their own opinions based on fact. We are not in the business of "forensically guessing" or "assuming".

Questions you need to answer confidently:

- How do you know this timestamp is accurate?

- What does this flag actually mean in the app's database?

- Could there be another explanation for this artifact?

- Have you tested this interpretation on other devices?

Examiners who follow the "verify, and then trust" approach can answer these questions because they've done the work to understand their evidence at a fundamental level.

Practical Implementation: A Verification Checklist

For every significant finding in your cases, ask yourself:

- Do I understand the underlying data structure?

- Have I examined the source files directly?

- Can I repeat this result on a test device?

- Am I clear about what this artifact actually represents or how it got there?

- Could there be alternative explanations for what I'm seeing?

- Have I documented my verification process?

If you can't check all these boxes, you're not ready to trust that finding.

Here is a checklist created by the wonderful Jessica Hyde (Founder & Owner of Hexorida.com) and myself to start you thinking about this critical process. Peer Review ChecklistThe Bottom Line: Your Job is Discovering TRUTH Through Data!

Remember this fundamental truth also: Your tools don't testify, you do.

When you take the witness stand, you're not just representing the output of a Cellebrite or Magnet report, you're presenting your professional analysis of digital evidence. That analysis must be built on a foundation of verified understanding, not assumed trust.

The "verify, and then trust" approach demands more work upfront, but it pays dividends in case quality, courtroom confidence, and professional credibility. In a field where the stakes are often someone's freedom or justice for victims, that extra effort isn't just worthwhile, it's an absolute MUST.

Validate your process. Verify your results. Then and only then, trust what you're presenting. Your cases, your testimony, and your professional reputation depend on getting this order right. Ask anyone on my forensics team at RCSD (Caitlin, Michael, Jordan, Brian or Trevor), and they'll tell you, this way is the only way!